Harvard Quilts

Harvard Historical Society, Harvard, MA

June 2000 through December 2000

June 2000 through December 2000

Harvard Quilts was an exhibition of 36 quilts belonging to the Harvard Historical Society and Harvard residents. Open houses and special programs brought record-breaking attendance and raised awareness within the community of the depth of the Society's collection. One local quilter donated a wall hanging for the purpose of a raffle. The proceeds from the raffle were nearly enough to pay for the purchase of archival storage boxes for the entire quilt collection.

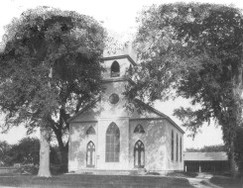

The Harvard Historical Society is housed in an 1832 meetinghouse built as the second house of worship of the Harvard Baptist Society. Founded in 1776, the Harvard Baptist Society served local farming families, and for nearly a century it was one of the only Baptist churches in the area. The Harvard Historical Society, which was founded in 1897, bought the building in 1967.

The Harvard Historical Society is housed in an 1832 meetinghouse built as the second house of worship of the Harvard Baptist Society. Founded in 1776, the Harvard Baptist Society served local farming families, and for nearly a century it was one of the only Baptist churches in the area. The Harvard Historical Society, which was founded in 1897, bought the building in 1967.

Patchwork 1885–1900. Cotton top and back;

wool ties.

A quilt is a textile normally composed of three layers: a backing, a layer of padding, and a top. The top of the quilt is where most of the design and color are found, and quilt tops can be made in several ways. Patchwork, as the name implies, consists of piecing together cut-fabric shapes to create a larger material. Through artful use of different fabrics and patchwork patterns, an infinite number of unique quilts can be made. The pattern on this quilt is a variation on King's Cross and in all likelihood was made from recycled men's shirting fabrics. Instead of connecting the layers of this quilt together with ornate quilting stitches, the quilter has decided to use knots of string. Tying quilts is not only quicker to execute than quilting but is more easily managed on a thick, warm quilt such as this. The 5-inch-wide border helps us date this quilt to the end of the 19th century.

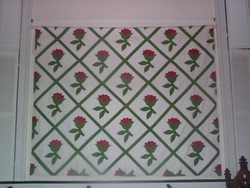

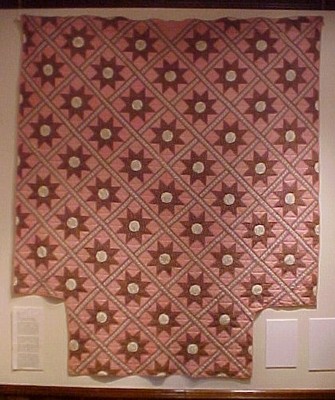

Appliquéd c 1850. Cotton front and back.

It was not unusual for men, as well as women, to participate in the execution of family quilts. To make this quilt, the quilter started with a solid ground fabric and applied the cut fabric shapes, which were hemmed under and sewn down with tiny, nearly invisible stitches. This quilt has only a very thin binding, according to the fashion of the time. The high quality of fabrics selected for the flowers, diagonal strip sets, and ground fabric suggest that this quilt was not intended for everyday use. It has been well cared for and survives in excellent condition with no fading of dyes.

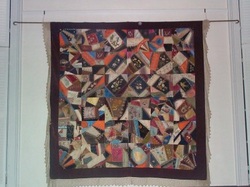

Crazy quilt 1850–1875. Silk front; cotton back; linen fringe

Crazy quilts get their name from the abstract arrangement of pieced and appliquéd fabric shapes that make up the quilt front. Although randomly pieced quilts are known from before the 19th century, crazy quilts reached their zenith of popularity and expression during Victorian times. The typical Victorian crazy quilt such as this contained fine dress fabrics, like silk velvets and challis, and an astonishing array of embroidery stitching and painted designs. The fringe is not unusual for a quilt dating to the mid-nineteenth century and this crocheted example is especially fine. This quilt was probably a combined effort of several makers, as witnessed by the embroidered signatures “Olive,” “Ida,” “C E B,” “Alice,” and “W. H. Y.”

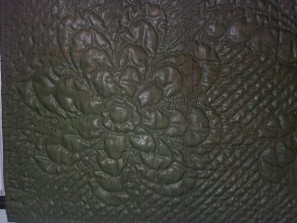

Glazed worsted quilt 1775–1800. Wool front and back.

This is the oldest quilt in the Harvard Historical Society's collection. Typical of fine late-eighteenth-century examples, it has a backing of mustard-colored, roughly woven wool, linen quilting thread, and a highly glazed, finely woven wool top. The top is pieced from three widths of fabric, which were sewn together prior to quilting. The olive color comes from the early method of overdying a yellow-dyed fabric with blue dye, and this fabric may have lost some of its blue hue due to light exposure.

The solid background is a perfect showcase for the remarkable sewing skills of this talented quilter. She would have used molds and patterns, as well as free-hand drawing to create the ornate feather and flower patterns. Some of the designs have been stuffed, a process consisting of separating the threads of the backing fabric and inserting padding to the desired height. This quilt also contains a heart motif, which was reserved exclusively for engagements and weddings, confirming that it was made for a special occasion.

Patchwork c 1850. Cotton.

Before the advent of synthetic dyes in the 1850s, textile manufacturers and home dyers had to rely on vegetable, insect, and mineral dyes. During the colonial period, huge taxes were collected on imported fabrics and dyestuffs, so native plants and insects were discovered that could render true and fast colors. The browns in this quilt may have come from tree bark or a mineral dye. Reds and pinks came from madder, pokeberries, and the now-lost Turkey red, which was more washfast than even our modern red dyes. The bright yellow used so prominently in this quilt could have been dyed with yelloweed, smartweed, peach or pear leaves, or more likely, from the mineral dye such as chrome yellow.

By the second and third quarters of the nineteenth century, quilting had become a rage. The Industrial Age brought an increase in affordable printed fabrics, which fed the quilters' appetites. Quilts were no longer limited to beds and were now found all over the house in forms such as seat covers, pillows, and lap blankets.

By the second and third quarters of the nineteenth century, quilting had become a rage. The Industrial Age brought an increase in affordable printed fabrics, which fed the quilters' appetites. Quilts were no longer limited to beds and were now found all over the house in forms such as seat covers, pillows, and lap blankets.

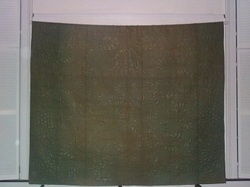

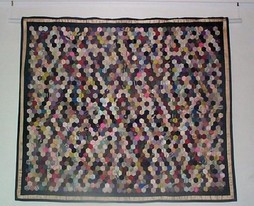

Mosaic Quilt 1875–1900. Silk front; cotton back.

The sewing machine also became widely available around 1860. This allowed quilters to piece together more quilts in a shorter period of time. Sometimes machine stitching was done in a contrasting color to the fabric in order to show it off. It was also common for crazy quilts to be partly assembled by machine and finished by hand to camouflage the evidence of this short cut. As helpful as a sewing machine was in the piecing and final binding of a quilt's edges, hand quilting was still the best way to connect the various layers within the body of the quilt.

This quilt is composed of 1.5–inch hexagons of fabric pieced together, each of which was made using a paper template. After the hexagons were all completed they were assembled into a quilt top. The quilt was completed with the addition of an interlining, a fine cotton backing, and a rich velvet and satin border. Although quilts such as this were often made from a collection of fabric scraps, the quality of the backing and border indicate these elements were probably purchased specifically for this project.

This quilt is composed of 1.5–inch hexagons of fabric pieced together, each of which was made using a paper template. After the hexagons were all completed they were assembled into a quilt top. The quilt was completed with the addition of an interlining, a fine cotton backing, and a rich velvet and satin border. Although quilts such as this were often made from a collection of fabric scraps, the quality of the backing and border indicate these elements were probably purchased specifically for this project.

You are looking at the back of an unfinished silk doll quilt from 1875-1900. The paper hexagons used to construct each block are still present. Executed in an identical technique to larger mosaic quilts, the minute, .5–inch hexagons would have required enormous skill and patience to construct. There is no backing, interlining, or border, which gives us a unique glimpse of the construction technique and the bright colors which have faded on the front.

Doll bed with mattress doll pillows. Cotton.

A young girl would make several quilt tops before she was of marrying age. Once her engagement was announced she would hold quilting bees to help finish her quilts in time for the wedding. The interlining and backing fabric were the most expensive parts of a quilt, as they were not made of scraps and often had to be bought. This expense, therefore, was not undertaken until the engagement was final, resulting in the survival of many unfinished quilts.

During colonial times the bed was one of the most important items of furniture in the home. It may have been placed in the parlor or main room on the ground floor, rather than in an upstairs bedroom. Quilts were often made to exactly fit the dimensions of the family bed. Most New Englanders were too poor for an elaborate bed and instead slept on rope beds, wooden pallets, or mattresses stuffed with rags, straw, or other plant material. Quilts were frequently used as both an undermat and a bed cover.

During colonial times the bed was one of the most important items of furniture in the home. It may have been placed in the parlor or main room on the ground floor, rather than in an upstairs bedroom. Quilts were often made to exactly fit the dimensions of the family bed. Most New Englanders were too poor for an elaborate bed and instead slept on rope beds, wooden pallets, or mattresses stuffed with rags, straw, or other plant material. Quilts were frequently used as both an undermat and a bed cover.

Scalloped basket quilt c 1850. Cotton.

This quilt combines the techniques of patchwork and appliqué: The baskets and background are pieced but the basket handles and bowknots and swags, which are composed of curved rather than straight lines, are appliquéd. The center frame contains the appliquéd initials “M. L. J” which may have been the maker or the person for whom the quilt was made. The birds have been done in the stuffed appliqué method, where the backing fabric is separated and padding stuffed inside.

T-shaped quilts such as the two below were made to fit four-poster beds without bunching of the quilt at the corner posts. The style is rarely seen outside New England. During colonial times affluent families had large four-poster beds in which young children often slept with their parents. For privacy, a four-poster bed could also be hung with bed curtains, which were looked upon as a sign of wealth.

The 8-inch-wide strips of fabric used in the quilt on the right give it a calm, uncluttered look. Minute patterns of dancing girls, raspberries, flowers, geometric shapes, and leaves can be appreciated for their overall design and coordinating colors. The tiny quilt on the left may have been specially made for a four-poster doll bed, or as a practice piece by a young girl yet to make a full-sized quilt. The pattern is a variation of “Geese in Flight” with the unruly “geese” flying off in several directions.

Record quilt 1867. Cotton.

The maker of this four-poster bed quilt in all likelihood did not intended for it to receive regular use. The incredible workmanship, effort, and expense that Eleanor Bolles Haskell put into creating it would have made it among her finest possessions. Although it is worn and soiled, there is evidence of much washing, which was possible thanks to the invention of indelible ink in the 1830s.

Album quilts of all types were the vogue from the 1840s through 1870s alongside the Victorian autograph book craze. They began as a collection of work done by several quilters and later on were more frequently wrought by a single hand from fabric amassed by several people. This record quilt is almost certainly made entirely by Eleanor Haskell, as the workmanship and her signature block indicate, as a way of recording events in the history of her family.

At the height of quilting in the mid-nineteenth century, textile manufacturers were producing printed cottons specifically for use by quilters. The diagonal strip sets in this quilt may have been cut from a striped fabric made for this purpose. The rusty reds and browns, as well as the familiar double pinks, were produced en masse by roller-printing machines in the third quarter of the nineteenth century in places like Lowell and Lawrence.

Album quilts of all types were the vogue from the 1840s through 1870s alongside the Victorian autograph book craze. They began as a collection of work done by several quilters and later on were more frequently wrought by a single hand from fabric amassed by several people. This record quilt is almost certainly made entirely by Eleanor Haskell, as the workmanship and her signature block indicate, as a way of recording events in the history of her family.

At the height of quilting in the mid-nineteenth century, textile manufacturers were producing printed cottons specifically for use by quilters. The diagonal strip sets in this quilt may have been cut from a striped fabric made for this purpose. The rusty reds and browns, as well as the familiar double pinks, were produced en masse by roller-printing machines in the third quarter of the nineteenth century in places like Lowell and Lawrence.

Signature quilt c. 1895. Cotton.

This extraordinary quilt contains the names of men and women from the town of Harvard. A study of the use of maiden and married names indicates that it was made in 1887. The name at the center of the quilt is that of an interim minister, James Morton, who headed the Harvard Baptist Society from 1885 to 1887. Unlike many signature quilts where different makers contributed and signed each block, this quilt appears to have been made and inscribed by a single hand. One possible explanation is that this quilt was used for a fundraising event. Members of a church or community may have been invited to sponsor a block of the quilt by making a monetary donation, in return for which their name would be inscribed. The quilt may have then been raffled off or donated along with the money that it raised. The pattern is known as “Double Monkey Wrench” and was ideal for use here because of the open center square.

Gatherings of people for the purpose of finishing a quilt were commonplace throughout the nineteenth century. Quilting bees, as they were known, brought women, men, and children together to share labor, exchange news, eat a meal, and socialize. Bees were also organized for events such as candle dipping, sheep sheering, and apple paring. Before a quilting bee could be called, one or more quilt tops had to be completed by the hostess. It was not uncommon for several quilts to be finished in a single day. Often quilting bees followed the engagement of a young woman who had to rush to finish her quilt tops before her wedding day. Betrothals were commonly announced at another woman's quilting bee.

Gatherings of people for the purpose of finishing a quilt were commonplace throughout the nineteenth century. Quilting bees, as they were known, brought women, men, and children together to share labor, exchange news, eat a meal, and socialize. Bees were also organized for events such as candle dipping, sheep sheering, and apple paring. Before a quilting bee could be called, one or more quilt tops had to be completed by the hostess. It was not uncommon for several quilts to be finished in a single day. Often quilting bees followed the engagement of a young woman who had to rush to finish her quilt tops before her wedding day. Betrothals were commonly announced at another woman's quilting bee.

Pieced and appliquéd quilt 1925–1950.

Cotton.

A quilting frame was usually made of wood and either suspended from the ceiling or balanced on chairs or a base. The backing fabric, interlining, and quilt top were stretched out and lashed to the frame. The best sewers in attendance were invited to sit around the frame and quilted the three layers together before the completed quilt was removed from the frame. All that remained was to cut the thread ends and bind the edges.

The great depression and two World Wars brought a renewed sense of economy that was familiar to the makers of quilts. Quilting kits and magazine patterns became more popular, which may be where this "Dresden Plate" quilt design originated. The simple form and small repeated block could be made in any number to create a quilt of the desired dimensions. The quilt has very thick padding and so has been tied rather than quilted. The wide borders are further indication that it is from the twentieth century.

The great depression and two World Wars brought a renewed sense of economy that was familiar to the makers of quilts. Quilting kits and magazine patterns became more popular, which may be where this "Dresden Plate" quilt design originated. The simple form and small repeated block could be made in any number to create a quilt of the desired dimensions. The quilt has very thick padding and so has been tied rather than quilted. The wide borders are further indication that it is from the twentieth century.

Quilt with crocheted overlay. c 1950. Cotton.

This unusual quilt contains elements of the traditional form, such as a pieced construction and top, interlining, and bottom layers. The crocheted overlays, reminiscent of quilt fringe or crocheted blankets, here have been applied directly over the top of the quilt in imitation of patchwork blocks. If you look carefully you can see a diagonal grid design within the crocheted overlays reminiscent of patchwork strip sets.

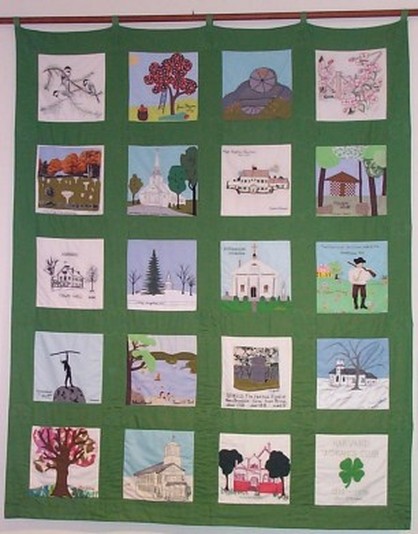

Quilts such as the one blow, depicting scenes of the town of Harvard, were a popular way to show patriotism around the time of the bicentennial in 1976. They hearken back to the signature and album quilts of the nineteenth century and, like earlier quilts, often contain an array of recycled materials. Here a green towel has been used to replicate the color and texture of vegetation. The shamrocks found throughout the quilt are the symbol of the Harvard Woman's club.

Quilts such as the one blow, depicting scenes of the town of Harvard, were a popular way to show patriotism around the time of the bicentennial in 1976. They hearken back to the signature and album quilts of the nineteenth century and, like earlier quilts, often contain an array of recycled materials. Here a green towel has been used to replicate the color and texture of vegetation. The shamrocks found throughout the quilt are the symbol of the Harvard Woman's club.